June 26, 2023: There was no geomagnetic storm on June 22nd. Nevertheless, the sky turned green over rural Colorado. Aaron Watson photographed the dramatic display from the West Elk Mountains:

“I woke up around midnight to crystal clear skies,” says Watson. “I noticed some wispy rays and, at first, I thought maybe it was noctilucent clouds. Upon closer inspection there was an intense green glow rippling across the entire sky.”

Although this looks a lot like aurora borealis, it is something completely different: airglow. Cameras with nighttime exposure settings can pick up the faint emission from anywhere on Earth even when geomagnetic activity is low. All that’s required is a very dark sky.

“Airglow is produced by photochemistry in Earth’s upper atmosphere,” says space scientist Scott Bailey of Virginia Tech. “And it is very interesting photochemistry.”

He explains: There is a layer of air about 95 km above Earth’s surface where two forms of oxygen mix together: Molecular oxygen (O2, the kind of oxygen we breathe) and atomic oxygen (O, a reactive species that is toxic to people). Both species are abundant in a wafer-thin zone only 10 km deep. O2 collides with O, exciting the atoms, which later relax by emitting green photons.

“I photographed it, too!” reports Christie Allen, who lives in southern Colorado. “Green rays were emerging from the Sangre de Cristo mountain range to our east.”

“At first I thought they were auroras,” she says, “but now I know it was airglow.”

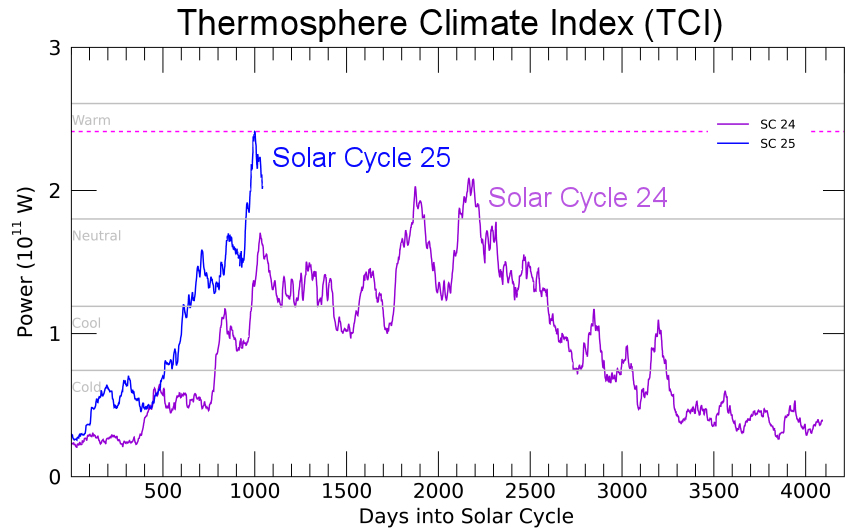

Although airglow does not require solar activity, there is a strong link to the solar cycle. As long ago as 1935, Lord Rayleigh realized that airglow peaks during years around Solar Maximum. Modern studies (e.g., 2011, 2015 and 2022) have confirmed the effect. Airglow is up to 40% brighter when the sun is most active.

“Solar activity boosts airglow by heating the upper atmosphere,” says Bailey. “Warmer air causes more collisions and, thus, more green light to emerge. This is why green airglow tends to be most intense around Solar Max.”

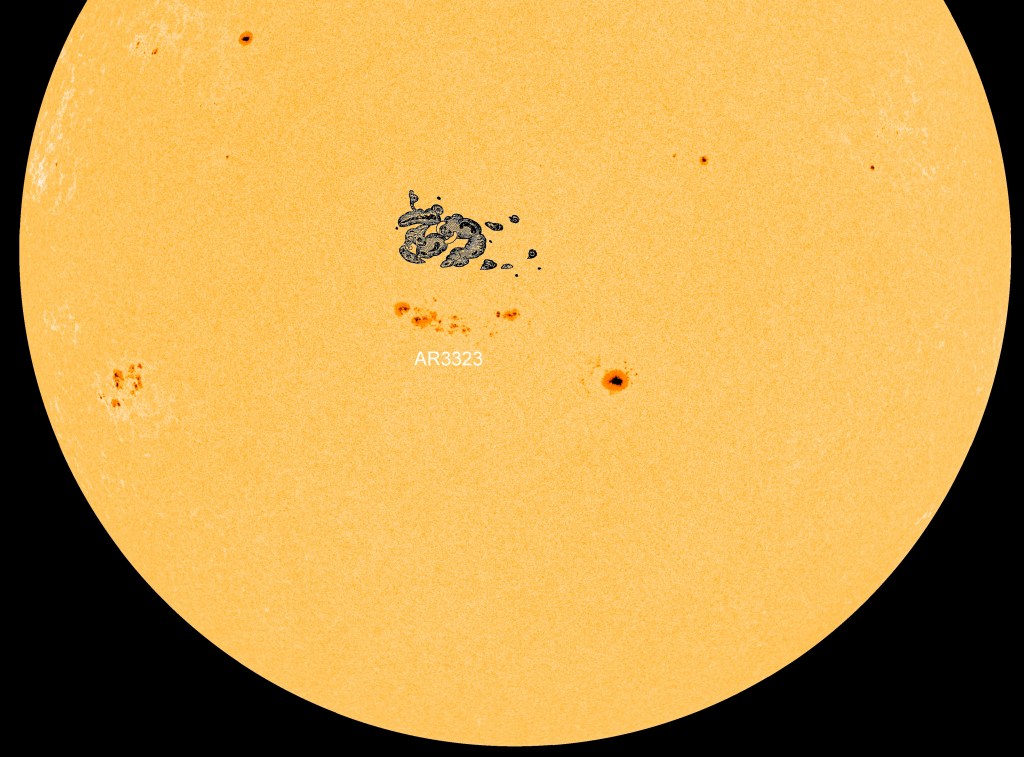

That means *now* is the time to look for airglow. Solar Cycle 25 is intensifying with Maximum perhaps less than a year away. Get away from city lights, wait for the Moon to set, and point your camera at the midnight sky. It might not be as dark as you think.

This story was brought to you by Spaceweather.com