Nov. 20, 2023: There’s a new phenomenon in the night sky: “SpaceX auroras.” They’re red, roughly spherical, and brightly visible to the naked eye for as much as 10 minutes at a time. “We are seeing 2 to 5 of them each month,” reports Stephen Hummel of the McDonald Observatory in Texas, who photographed this one on Nov. 3rd:

Spoiler alert: They’re not auroras. The bright red balls are caused by SpaceX rockets burning their engines in the ionosphere.

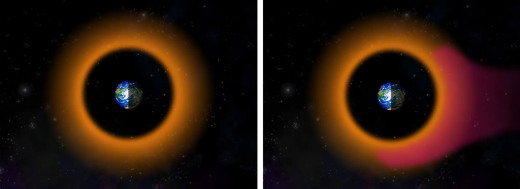

The phenomenon is closely related to something we reported earlier this year. Falcon 9 rockets leaving Earth can “punch a hole in the ionosphere.” The ionosphere is a layer of ionized gas surrounding our planet; it is crucial to over-the-horizon shortwave radio communication and can affect the quality of GPS signals. Water-filled rocket exhaust can quench local ionization by as much as 70%, erasing the ionosphere along the rocket’s path. For reasons having to do with chemistry, ionospheric holes emit a red glow (630 nm).

“SpaceX auroras” are exactly the same–except instead of rockets going up, they are caused by rockets coming down. The second stage of the Falcon 9 rocket burns its engines in order to de-orbit and return to Earth, creating an ionospheric hole as it descends.

“We first noticed these SpaceX de-orbit burns over the McDonald Observatory in February 2023,” says Boston University space physicist Jeff Baumgarder, who has been studying ionospheric holes for more than 40 years. “The engine burns are only about 2 seconds long, just enough delta V to bring the second stage down over the south Atlantic Ocean. These burns happen ~90 minutes ( ~one orbital period) after launch. During the burn, the engine releases about 400lbs of exhaust gasses, mostly water and carbon dioxide. All this happens at ~300km altitude, near the peak of the ionosphere, so a significant hole is made.”

“The resulting ‘auroras’ can be very bright, easily visible with the naked eye and much brighter than Starlink satellites themselves, although only for a few seconds,” notes Hummel.

The question is, are SpaceX auroras good or bad?

Hummel is the McDonald Observatory Dark Skies Sr. Outreach Program Coordinator, so naturally he’s concerned about the effect these events may have on observational astronomy.

“The frequency of these red clouds could increase as SpaceX targets more launches in the future,” says Hummel. “Their impact on astronomical science is still being evaluated. Starlink satellites are a known issue, but the effects of the rocket launches themselves are a growing area of attention.”

For Jeff Baumgarder, who has his own dedicated camera at McDonald, the events are a golden opportunity for research.

“The saying ‘one person’s signal is another person’s noise’ is appropriate here,” says Baumgardner. “We are delighted with the rocket burns. They give us an opportunity to explore how space traffic affects the ionosphere. The ionospheric density is different night to night, so we can learn something about the efficiency of the chemistry by observing many events.”

Other sky watchers are beginning to see SpaceX auroras as well. Are you one of them? Submit your pictures here.