May 21, 2025: (Spaceweather.com) More than 14 thousand years ago, there was a solar storm so big, trees still remember it. Dwarfing modern solar storms, the event would devastate technology if it happened again today. Spoiler alert: It could.

Above: Subfossil trees along the banks of the Drouzet river in France [ref]

The record-strong storm is described by a paper in the upcoming July 2025 edition of the peer-reviewed journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters. It occured in 12,350 BC and is classified as a “Miyake Event.”

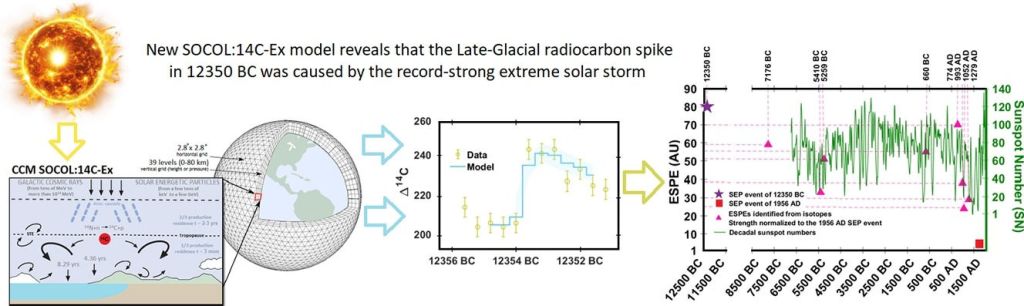

Miyake Events are solar storms that make the Carrington Event of 1859 look puny. Trees “remember” them in their rings, which store the carbon-14 created by gargantuan storms. At least six Miyake Events have been discovered and confirmed since Fusa Miyake found the first one in 2012. The list so far includes 664-663 BC, 774 AD, 993 AD, 5259 BC, 7176 BC, and 12,350 BC.

The Miyake Event of 12,350 BC is especially intriguing. It appears as a carbon-14 spike in Scots Pine trees along the banks of the Drouzet river in France, with a matching beryllium-10 spike in Greenland ice cores. The event was global and, based on the size of the spikes, very big.

At first, no one could say how big the storm was because it happened during the Ice Age.

Carbon-14 storage is complicated. When a solar storm creates carbon-14 in the upper atmosphere, the radioisotope doesn’t immediately appear in the woody flesh of trees. Getting there involves months to years of atmospheric circulation influenced by climate and geography, and even then the carbon-14 has to arrive during the tree’s growing season, otherwise it won’t be “taken up.” High-altitude trees are favored because they encounter the carbon-14 first, while different species each have their own sensitivity.

All these factors are a harder to tease out in the Ice Age. Most known Miyake Events occurred after the Ice Age, during the Holocene, a period of relatively stable and warm climate starting about 12,000 years ago. Climate scientists have atmospheric circulation models for the Holocene, so interpreting Miyake Events in 7176 BC, 5259 BC, 664-663 BC, 993 AD, 774 AD was relatively straightforward. Not so, the event of 12,350 BC.

To solve this problem, Kseniia Golubenko and Ilya Usoskin from the University of Oulu in Finland developed a chemistry-climate model (SOCOL:14C-Ex) specifically for Ice Age solar storms. It takes into account ice sheet boundaries, sea levels, and geomagnetic fields that existed during the Pleistocene’s Late Glacial period. Using this model, they were able to interpret tree ring data for 12,350 BC.

According to their paper, 12,350 BC is the biggest Miyake Event yet. It produced a hailstorm of solar particles 500 times greater than the most intense solar particle storm recorded by modern satellites in 2005. During the 2005 event, an airline passenger flying over the poles might have received a year’s worth of sea-level cosmic radiation in just one hour. During the 12350 BC event, the same dose would have been received in a mere eight seconds.

This would seem to set a new standard for worst-case scenarios in space weather. However, the real news is deeper: The door to the Ice Age has been kicked open by SOCOL:14C-Ex. Older tree rings may now be interpreted with confidence, potentially revealing even worse storms.

Stay tuned for more news from the trees.