July 21, 2025 (Spaceweather.com): Carl Sagan famously said, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.” But he never said we couldn’t discuss extraordinary claims without extraordinary proof. In that spirit, we review a new draft paper by Avi Loeb and colleagues, which asks whether interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS might be a spaceship.

Avi Loeb is a Harvard astronomy professor who became a household name in 2017 after the discovery of ‘Oumuamua, the first known interstellar object to pass through our solar system. While most scientists offered natural explanations, Loeb made headlines by suggesting it could be an artificial probe from an alien civilization.

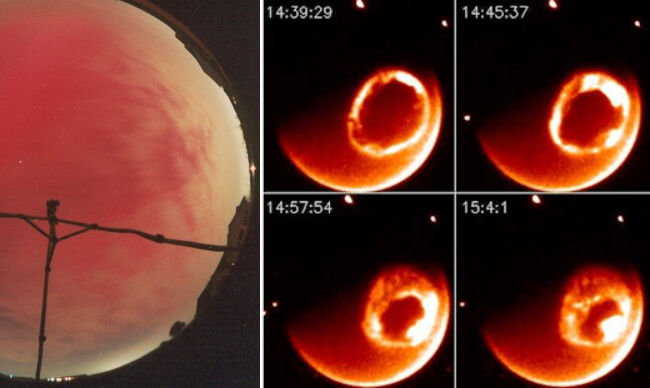

Above: This artist’s concept shows how ‘Oumuamua is usually depicted: as a cigar-shaped asteroid.

The idea might have been dismissed outright if it came from someone less credentialed. But Loeb’s Harvard affiliation lent it gravitas—and he had a point. ‘Oumuamua’s strange cigar-like shape and unexplained acceleration fit the Hollywood stereotype of a spacecraft. It sped up slightly as it left the solar system, possibly due to outgassing like a comet. Yet no gas or dust was ever seen.

Loeb’s reception has been frosty. Many mainstream researchers refuse to even mention his ideas in published papers, arguing that they have been debunked. But Loeb hasn’t backed down. He pioneered Project Galileo in 2021 to search the skies for technological artifacts. He has even searched the ocean floor. In mid-2023, Loeb announced the recovery of metallic spherules in the Pacific, arguing that they may be fragments from an artificial interstellar meteor. (Others disagree.)

Now Loeb is looking at interstellar object 3I/ATLAS as a potential piece of alien technology. In a paper co-authored by Adam Hibberd and Adam Crowl, he lays out nine ideas consistent with it being an intentional alien visitor. We review some of them here:

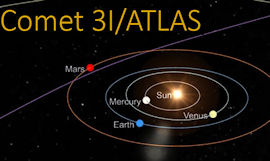

1. The orbit of 3I/ATLAS is strangely parallel to Earth’s. It lies within 5 degrees of the ecliptic plane–a coincidence with odds of less than 0.2%. The ecliptic plane is a narrow target, and the odds of a random interstellar comet hitting it are indeed low.

2. 3I/ATLAS will approach three planets during its visit: Venus (0.65au), Mars (0.19au) and Jupiter (0.36au). The cumulative probability of such a triple encounter is about 0.005%. However, it is the kind of pattern you might expect from a planetary survey.

3. 3I/ATLAS is on course to avoid Earth. At perihelion (closest approach to the sun), 3I/ATLAS and Earth will be on opposite sides of the sun. “This could be intentional to avoid detailed observations from Earth-based telescopes when the object is brightest or when gadgets are sent to Earth from that hidden vantage point,” writes Loeb in a blog post. We believe this statement speaks for itself.

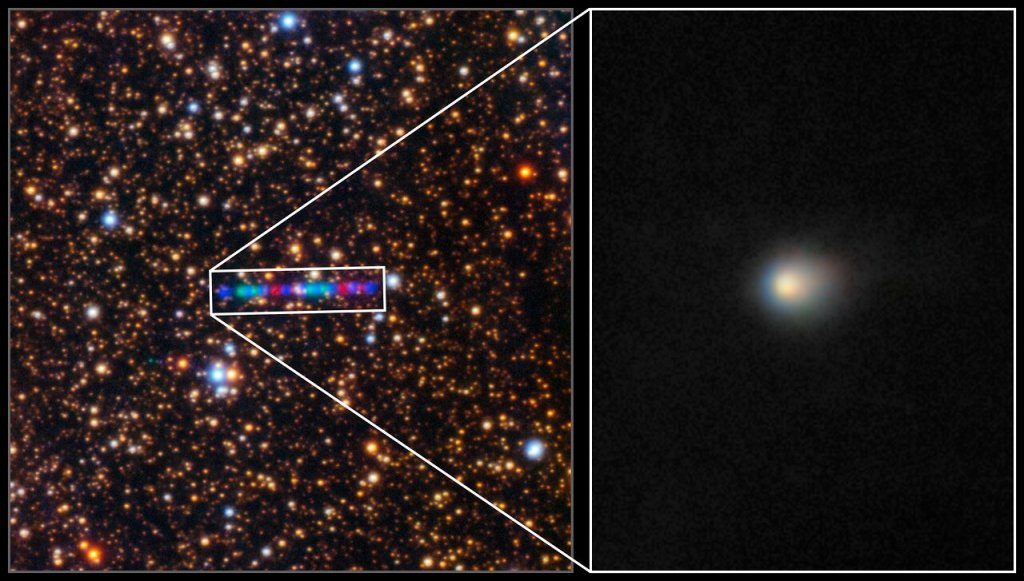

4. Although most astronomers believe 3I/ATLAS is a comet, “no spectral features of cometary gas are found in spectroscopic observations of 3I/ATLAS,” notes Loeb. This is far from conclusive. For one thing, 3I/ATLAS is still very far away, and its spectral features may simply be too faint to observe. More importantly, new images from the Gemini North Telescope show 3I/ATLAS looking exactly like a comet with a normal gaseous envelope. Update: Hubble agrees.

Above: Gemini North picture of 3I/ATLAS. It looks like a comet.

5. 3I/ATLAS has two chances to perform an Oberth maneuver. During its close approaches to the sun and Jupiter, 3I/ATLAS could fire its engines (if any) and become a permanent resident of the Solar System. That’s exactly what an exploratory probe might want to do.

Taken together, these points read more like a collection of curious coincidences than compelling evidence of alien tech. Even the authors admit as much: “This paper is contingent on a remarkable but, as we shall show, testable hypothesis, to which the authors do not necessarily ascribe, yet is certainly worthy of an analysis and a report,” they wrote.

We agree. It’s okay to talk about these extraordinary claims, even if we don’t believe them–yet. Stay tuned for updates as Loeb’s hypotheses are put to the test.