July 14, 2022: You know a solar flare is strong when even the Voyager spacecraft feel it. Twenty-two years ago today (July 14, 2000) the sun exploded with so much force, it sent shockwaves to the edge of the solar system.

Earth was on the doorstep of the blast, nicknamed the “Bastille Day Event” because it happened on the national day of France. Subatomic particles accelerated by the flare peppered satellites and penetrated deep into Earth’s atmosphere. Radiation sensors on Earth’s surface registered a rare GLE–a “ground-level event.”

|  |

“People flying in commercial jets at high latitudes would have received double their usual radiation dose,” says Clive Dyer of the University of Surrey Space Centre in Guildford UK, who studies extreme space weather. “It was quite an energetic event–one of the strongest of the past 20 years.”

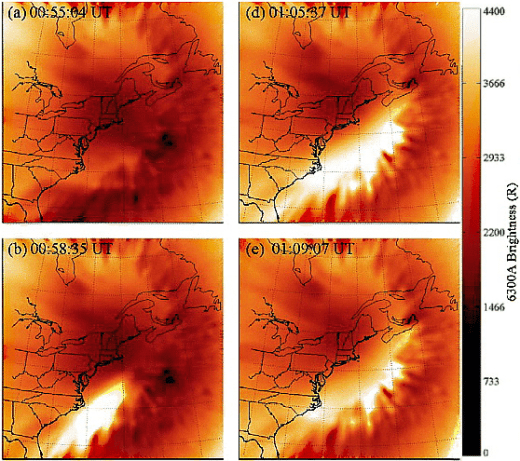

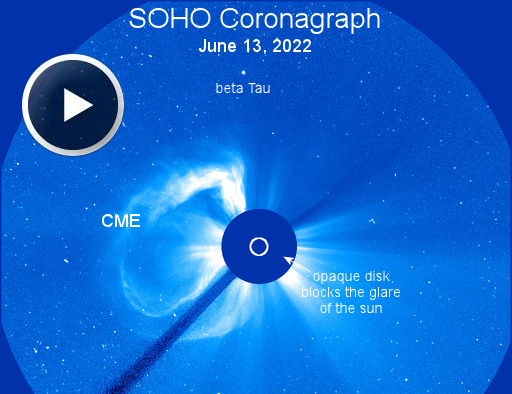

A day later the CME arrived. Impact on July 15th sparked an extreme (Kp=9) geomagnetic storm. The sun had just set on the east coast of North America when the first auroras appeared.

“I was out in the yard doing chores and saw bright red auroras straight overhead,” recalls Uwe Heine of Caswell County, North Carolina. “I called over to our neighbor, Carrie, who was also outside. I told her those were not sunset colors. It was an aurora, and super rare to see this far south!”

In New York, the sky exploded with light, recalls Lou Michael Moure. “I was living on Long Island at the time. A family member came running into my room, begging me to come outside to see ‘the sky on fire.’ The sky truly looked as if it was ablaze. Hues of white and green eventually gave way to reds that blanketed the heavens from horizon to horizon.”

By the time the storm was over on July 16th, auroras had been sighted as far south as Texas, Florida and Mexico.

A few other storms of the Space Age have have been equally strong, but the Bastille Day Event is special to researchers. It was the first major solar storm after the launch of SOHO, the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory. Data from the revolutionary young satellite taught researchers a lot, very quickly, about the physics of extreme flares.

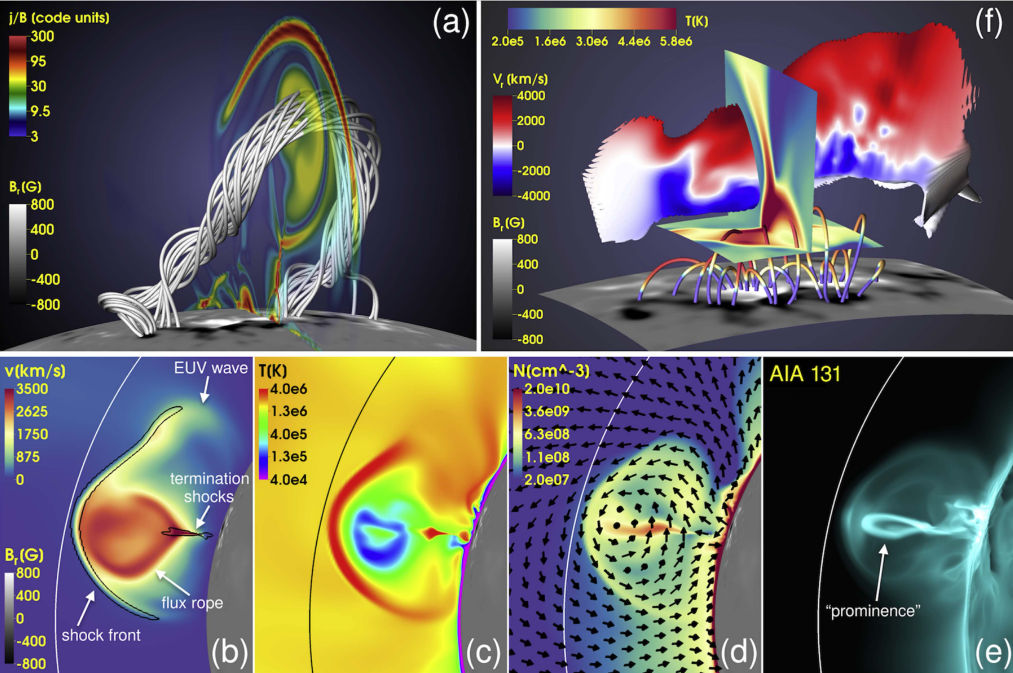

Tibor Török of Predictive Science, Inc., is one of many researchers still studying the Bastille Event decades later. “The event took place close to disk center, so we had a great view of the action,” he says. Török recently applied a modern magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) computer model to some of the data, and found that 1033 ergs of magnetic energy were released in the explosion–about the same as a thousand billion WWII atomic bombs.

No wonder the Voyagers felt it.

It took the Bastille Day CME months to reach the distant spacecraft. Voyager 2 felt it 180 days later, Voyager 1 took 245 days. Being near the edge of the solar system, both spacecraft were naturally bathed in high levels of cosmic rays. The CME swept aside that ambient radiation, creating a temporary reduction called a “Forbush Decrease.” Conditions returned to normal 3 to 4 months later and, finally, the storm was over.

Could another Bastille Day Event be in the offing? Solar Cycle 25 is ramping up, with a new Solar Max expected in 2025. Stay tuned.

more aurora photos: from Ronnie Sherrill of Troutman, North Carolina