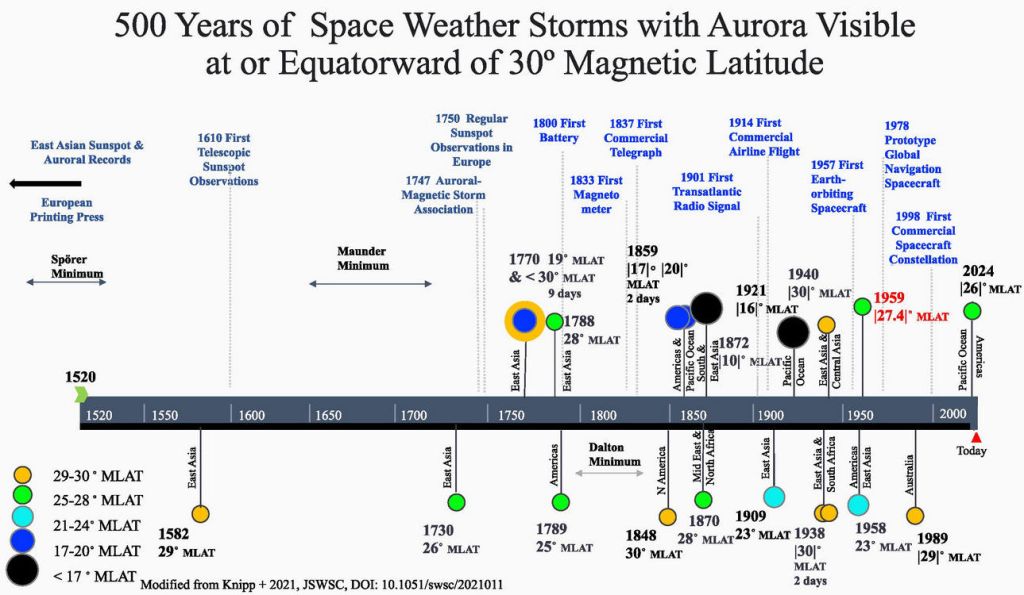

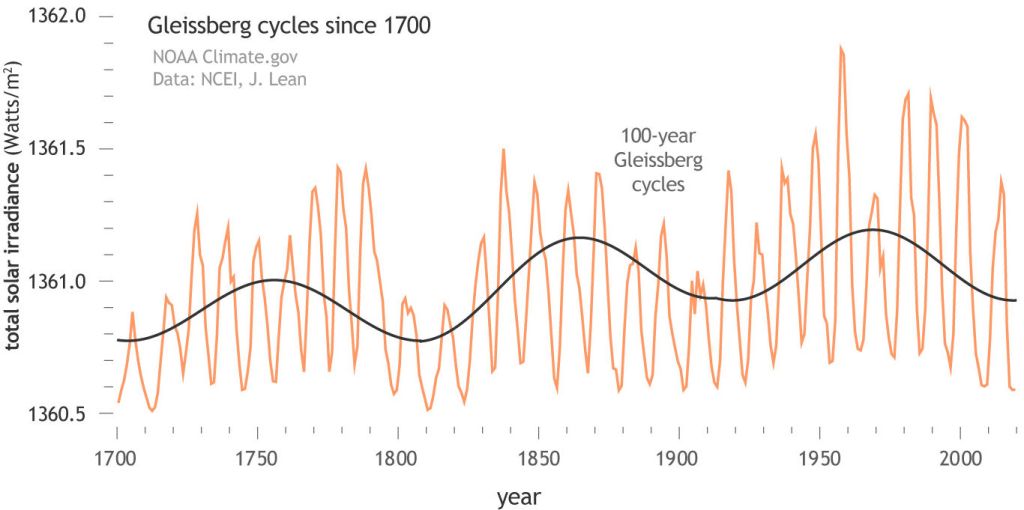

May 6, 2025: (Spaceweather.com) If you’ve been enjoying the auroras of Solar Cycle 25, we’ve got good news. The next few solar cycles could be even more intense–the result of a little-known phenomenon called the “Centennial Gleissberg Cycle.”

You’ve probably heard of the 11-year sunspot cycle. The Gleissberg Cycle is a slower modulation, which suppresses sunspot numbers every 80 to 100 years. For the past ~15 years, the sun has been near a low point in this cycle, but this is about to change.

New research published in the journal Space Weather suggests that the Gleissberg Cycle is waking up again. If this is true, solar cycles for the next 50 years could become increasingly intense.

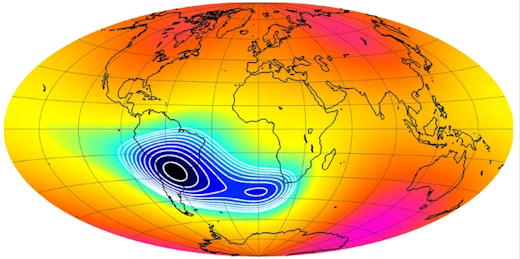

“We have been looking at protons in the South Atlantic Anomaly,” explains the paper’s lead author Kalvyn Adams, an astrophysics student at the University of Colorado. “These are particles from the sun that come unusually close to Earth because our planet’s magnetic shield is weak over the south Atlantic Ocean.”

Above: The South Atlantic Anomaly (blue) is a weak spot in Earth’s magnetic field where particles from the sun can come relatively close to Earth [more]

It turns out that protons in the South Atlantic Anomaly are a “canary in a coal mine” for the Gleissberg Cycle. When these protons decrease, it means the Gleissberg Cycle is about to surge. “That’s exactly what we found,” says Adams. “The protons are clearly decreasing in measurements we obtained from NOAA’s Polar Operational Environmental Satellites.”

Protons in the South Atlantic Anomaly are just the latest in a growing body of evidence suggesting that the “Gleissberg Minimum” has passed. Current sunspot counts are up; the sun’s ultraviolet output has increased; and the overall level of solar activity in Solar Cycle 25 has exceeded forecasts. It all adds up to an upswing in the 100-year cycle.

It also means that Joan Feyman was right. Before she passed away in 2020, the pioneering solar physicist was a leading researcher of the Gleissberg Cycle, and she firmly believed that the centennial oscillation was responsible for the remarkable weakness of Solar Cycle 24 (2012-2013). In a seminal paper published in 2014, she argued that the minimum of the Gleissberg Cycle fell almost squarely on top of Solar Cycle 24, making it the weakest cycle in 100 years. The tide was about to turn.

The resurgence of the Gleissberg Cycle makes a clear prediction for the future: Solar Cycles 26 through 28 should be progressively intense. Solar Cycle 26, peaking in ~2036, would be stronger than current Solar Cycle 25, and so on. The projected maximum of the Gleissberg Cycle is around 2055, aligning more or less with Solar Cycle 28. That cycle could be quite intense.

“With a major increase in launch rates, it’ll be important to plan for changes to the space environment that thousands of satellites and spacecraft are flying through from all sides,” says Adams. “Solar activity and particle fluxes could all be very different in the decades ahead.”

For more information, read Adams’s original research here.