July 14, 2025: You know a solar flare is strong when even the Voyager spacecraft feel it. Twenty-five years ago, on July 14, 2000, the sun unleashed one of the most powerful solar storms of the Space Age—an event so intense, its shockwaves rippled all the way to the edge of the solar system.

Voyager 2 felt the explosion 180 days later; Voyager 1, 245 days. The debris was still coherent and traveling faster than 600 km/s (1.9 million mph) when it slammed into the two spacecraft—then more than 9 billion kilometers from the sun.

Here on Earth, the effects were almost immediate. Within minutes, extreme ultraviolet and X-ray radiation bathed our planet and its satellites. Ground-based sensors registered a rare GLE (ground-level event) as energetic particles cascaded through the atmosphere.

“People flying in commercial jets at high latitudes would have received double their usual radiation dose,” recalled Clive Dyer of the University of Surrey Space Centre. “It was quite an energetic event—one of the strongest of its time.”

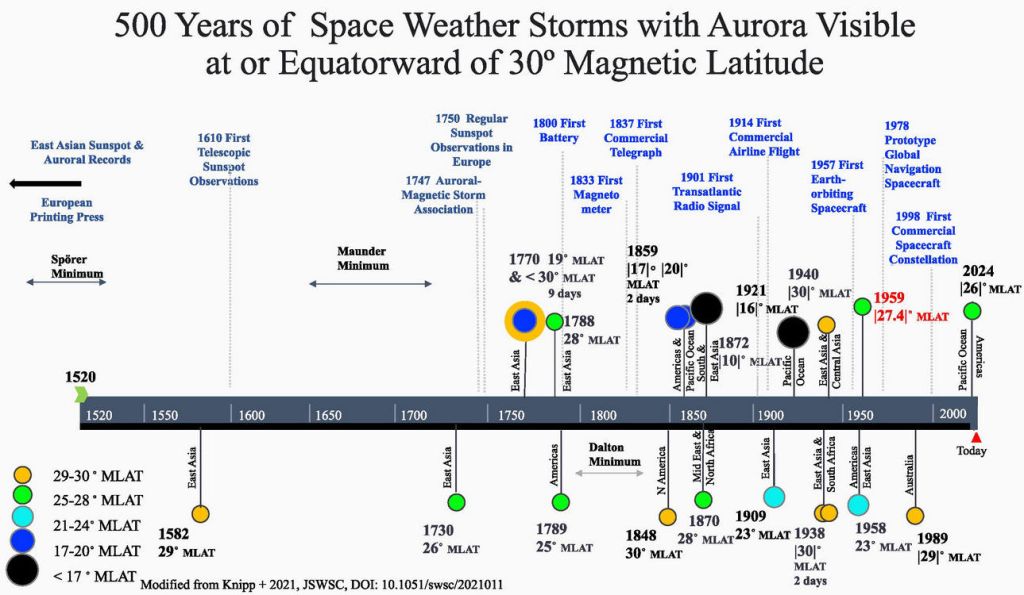

Because the flare happened on July 14th, it’s called “The Bastille Day Event” after France’s national holiday. However, auroras did not appear until the following day, July 15th, when a coronal mass ejection (CME) arrived. The 1500 km/s impact triggered an extreme geomagnetic storm (Kp=9).

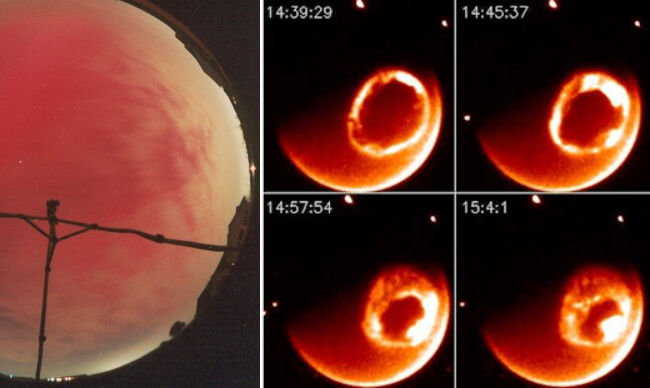

Above: Auroras on July 15, 2000, photographed by (left) Ronnie Sherrill in North Carolina and (right) NASA’s IMAGE spacecraft.

In New York, Lou Michael Moure remembers his sky catching fire: “I was living on Long Island. A family member ran into my room, shouting about ‘the sky on fire.’ Sure enough, the sky blazed white, green, then red from horizon to horizon.” In North Carolina, Uwe Heine was doing yardwork when bright red auroras appeared straight overhead: “I told our neighbor those weren’t sunset colors. It was an aurora—and super rare this far south!”

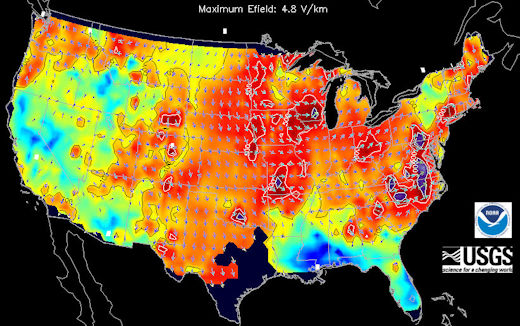

By the time the storm ended on July 16th, auroras had been sighted as far south as Texas, Florida, and even Mexico.

The Bastille Day Event was important because, for the first time in history, spacecraft throughout the solar system were equipped with instruments capable of studying such a storm. Most notably, it was the first major solar storm observed by SOHO, the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, which gave researchers an unprecedented look at how extreme flares unfold and evolve.

|  |

| Above: SOHO images of the X5.7-class Bastille Day solar flare (left) and CME (right). “Snow” in the images is a result of energetic protons hitting the spacecraft | |

Later studies described how an X5.7-class flare, erupting near the center of the solar disk, released 10³³ ergs of magnetic energy—equivalent to a thousand billion WWII-era atomic bombs. The resulting CME generated a massive barrier of magnetic field and plasma, which swept away galactic cosmic rays as it raced through the heliosphere. Even the Voyagers felt this unusual dip in cosmic radiation, known as a Forbush Decrease.

Could it happen again? It could happen again this week. We’re currently near the peak of Solar Cycle 25, and another X-flare is well within the realm of possibility.

Happy Bastille Day.