This week the internet is buzzing with headlines like “Mysterious Object Is Up to No Good While It’s Hidden Behind the Sun.” They’re referring to interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS. Harvard astronomer Avi Loeb and others have suggested it might be a spaceship deliberately hiding from humans. There’s just one problem with this argument: We can still see it from Earth.

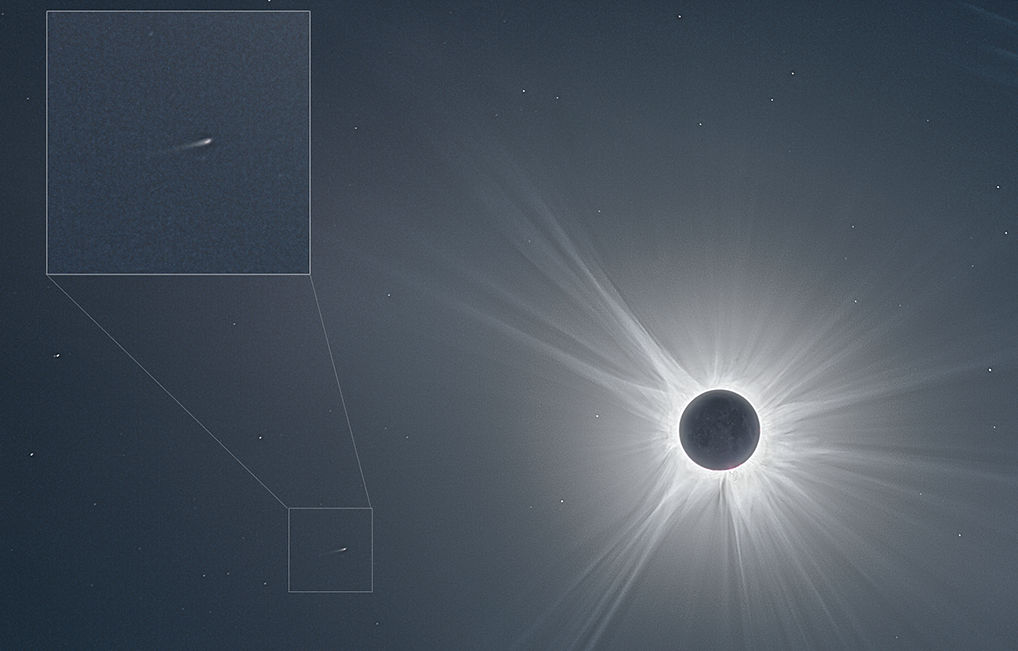

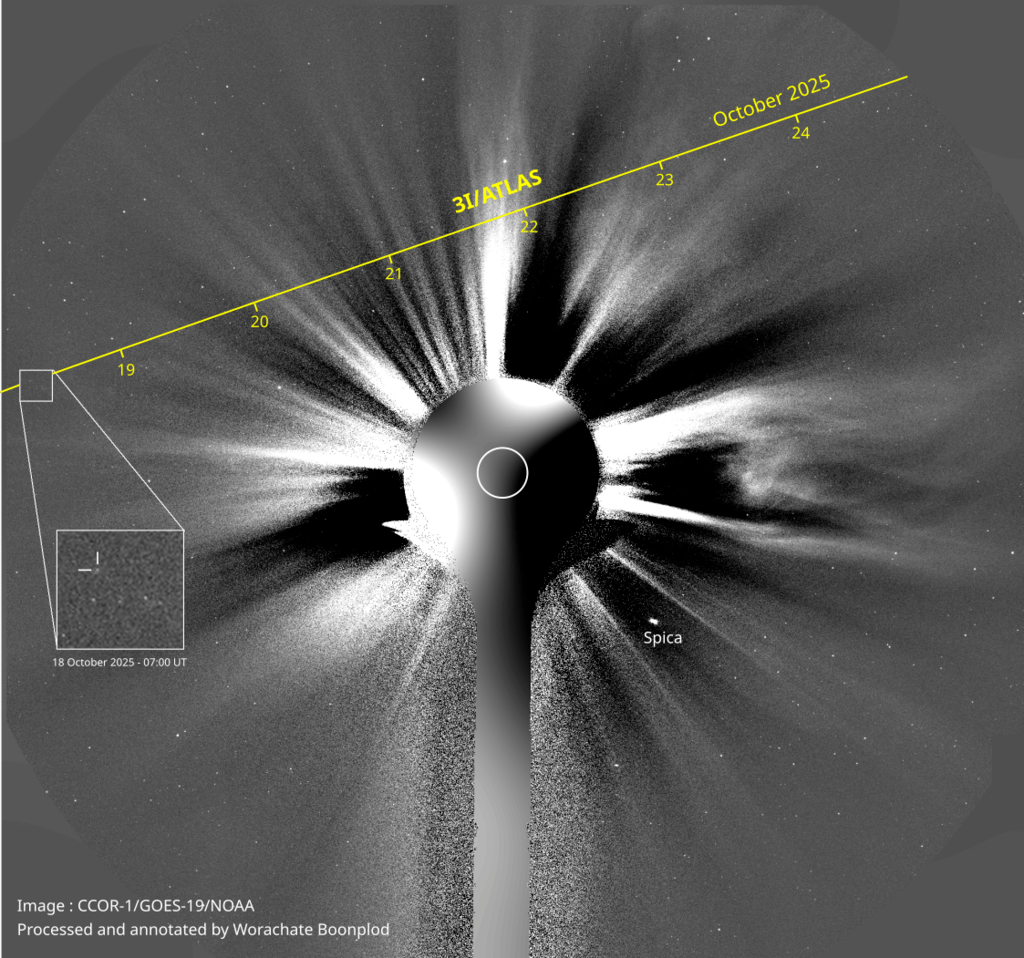

For example, the CCOR-1 coronagraph onboard NOAA’s GOES-19 satellite is tracking the comet and monitoring its brightness:

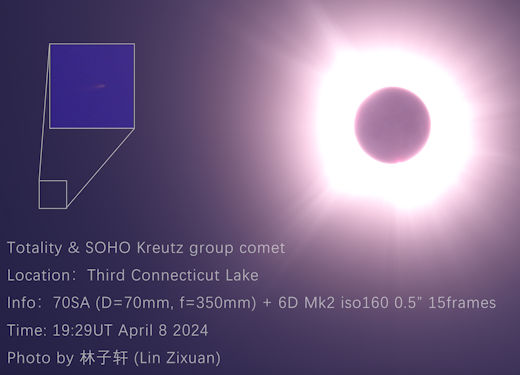

So is NASA’s quartet of PUNCH spacecraft, and coronagraphs onboard the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO, not far from Earth). Comet 3I/ATLAS is under constant surveillance.

“Unless 3I/ATLAS fades substantially in the next couple of days, we should be able to keep eyeballs on it right through its perihelion (closest approach to the sun),” says coronagraph expert Karl Battams.

Tracking the comet is not easy because it is so faint. Battams explains how it is done: “Objects at the threshold of detection like 3I/ATLAS are a challenge for coronagraphs. We often have to employ image stacking techniques. For this to work, we have to have a very precise understanding of the pointing and distortion of the telescopes so that we can find the exact pixels that correspond to the comet. It gets fiddly, but we make it work.”

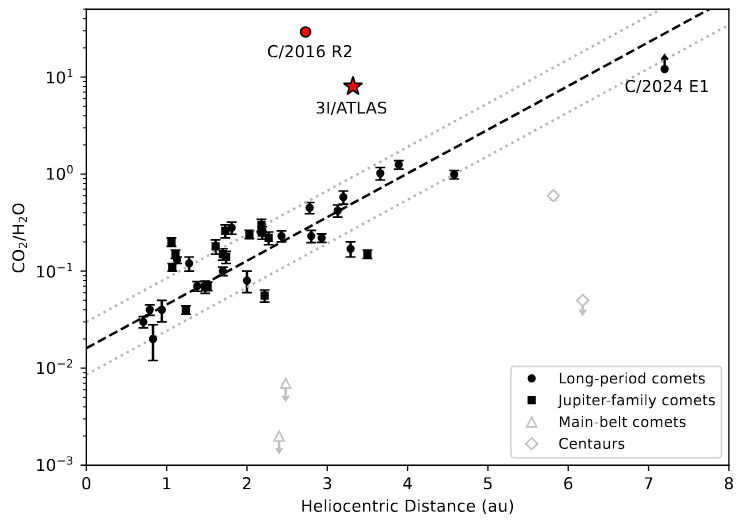

If 3I/ATLAS changes direction or surges in brightness, we will know. So far, it’s acting like a comet. T. Marshall Eubanks from Space Initiatives Inc assembled this light curve, including recent data from CCOR-1 and PUNCH:

These data confirm that 3I/ATLAS is following a fairly standard model of comet brightness with contributions from gas and dust. If this is a spacecraft, it is wearing an uncanny disguise.

In December, 3I/ATLAS will emerge from the glare of the sun. Telescopes on Earth’s surface can then rejoin the monitoring effort. Our bet: They will see a comet, not a spaceship. Stay tuned.