July 17, 2025 (Spaceweather.com): Astronomers come in all shapes and sizes–even invertebrates. A new study published in Nature reveals that Australian moths can see and decipher the night sky. They pay particular attention to the Milky Way and seem capable of navigating using the Carina nebula as a visual landmark.

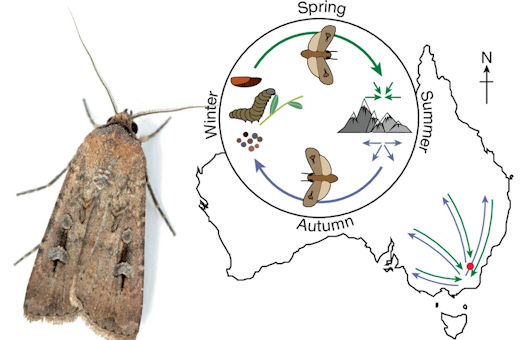

Above: A male Bogong moth and a diagram of their annual migration.

Every spring in southeast Australia, billions of Bogong moths take flight under cover of darkness. It’s the beginning of an epic migration as much as 1,000 kilometers long. Their destination: a small cluster of caves in the Australian Alps–places the moths have never visited before, yet somehow navigate to with remarkable precision. Their compass, it turns out, is the night sky itself.

Reaching this conclusion required the researchers to do something you probably don’t want to think about too closely: They attached the moths to tiny little tethers. Moths could lift off and pick a direction, but not escape.

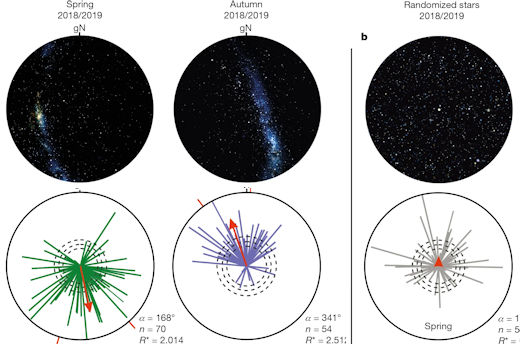

The experiment unfolded inside a special moth planetarium (pictured right). Star patterns were projected onto an overhead screen, while the ambient magnetic field was nulled by Helmholtz coils, guaranteeing that the participants could not “cheat” using magnetic navigation. When shown a normal star field, the moths oriented in the correct direction. But when the stars were scrambled into random patterns, they lost their bearings.

To dig deeper, the researchers recorded activity from visual neurons in the moths’ brains as a projected night sky rotated overhead. Neurons fired most strongly when the stars aligned with the moth’s inherited migratory heading. Some neurons were tuned to the brightest region of the Milky Way (especially near the Carina nebula) suggesting that this band of starlight is a visual landmark.

Clouds produced the next revelation: Bogong moths remained oriented even when stars were hidden. In those cases, they relied on Earth’s magnetic field instead, revealing a dual-compass system similar to that of migratory birds. When both stellar and magnetic cues were removed, the moths became disoriented again.

Upper row: Laboratory-projected night skies during spring and autumn, and an autumn sky with its stars randomly arranged. Lower row: The moths’ reaction to each sky.

In recent years, scientists have discovered that many creatures are guided by the stars. In addition to humans, the list includes migratory songbirds, possibly seals, dung beetles, cricket frogs, and now Bogong moths. The list of lifeforms guided by magnetism is even longer, ranging in size from microbes to whales.

You can read the original research here.