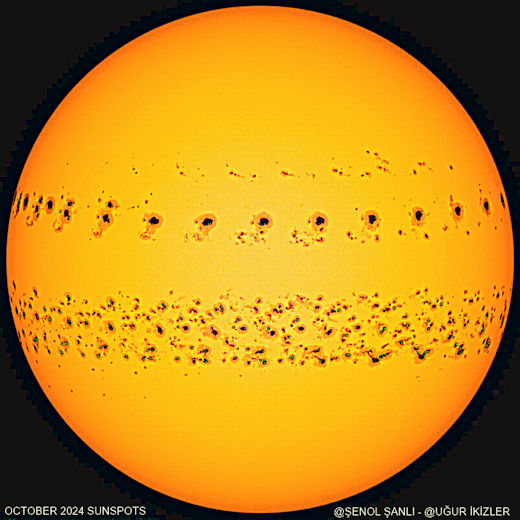

Nov. 4, 2024: At the end of October, amateur astronomer Senol Sanli made a composite 31-day image of the month’s sunspots. Take a look. Notice anything?

The two hemispheres of the sun are not the same. There’s a lopsided distribution of sunspots, with three times more in the south compared to the north. According to hemispheric sunspot data from the Royal Observatory of Belgium (WDC-SILSO), October was the fifth month in a row the sun’s southern hemisphere significantly outperformed the north. You can see the same pattern visually in composite images from September, August, July, and, to a lesser extent, June 2024.

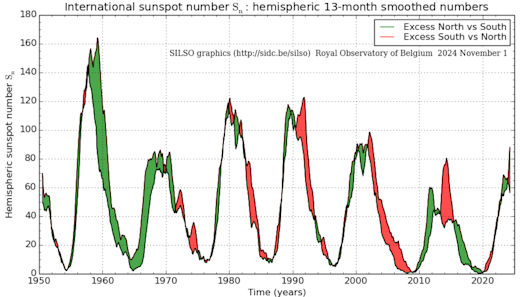

What’s going on? Solar physicists have long known that the two hemispheres of the sun don’t always operate in sync. Solar Max in the north can be offset from Solar Max in the south by as much as two years, a delay known as the “Gnevyshev gap.” The assymetry is illustrated in this graph of north-vs-south sunspot numbers from the last 6 solar cycles:

Is the sun’s southern hemisphere experiencing its Solar Max right now? Maybe. We won’t know for sure until years from now when we can look back and see the final shape of Solar Cycle 25. Meanwhile, stay tuned for more southern sunspots.