June 5, 2019: On June 30, 1908, in broad daylight, a meteoroid hurtled out of the blue sky over Russia’s Tunguska river and exploded, leveling a forest. The event, which researchers are still studying today, kickstarting a new field of astronomy: Daytime meteor showers1.

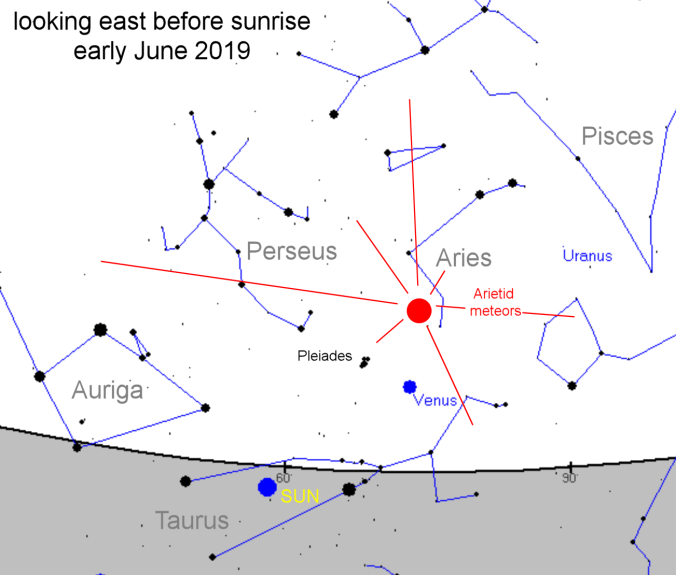

Most people don’t know it, but some of the strongest meteor showers of the year happen when the sun is up. In fact, one of them is underway now. Today’s sky map from Canada’s Meteor Orbit Radar (CMOR) in western Ontario shows a hot spot in the constellation Aries only 20 degrees from the sun.

Yes, this picture is real. It shows a daylight fireball over the Tetons behind Jackson Lake, Wyoming, in the summer of 1972. Credit & Copyright: James M. Baker

“These are Arietid meteors, and they peak every year in early June as Earth passes through a debris stream linked to the unusual comet 96P/Machholz,” says professor Peter Brown of the University of Western Ontario. “At their peak on June 7th, we expect our radar to detect one Arietid every 20 seconds. This makes them the 5th strongest radar shower of the year.”

In fact, people can see daylight meteors–a few at least. The trick is to look just before dawn when the shower’s radiant is barely above the horizon and the sun is barely below.

“The Arietids an observer would see before dawn are quite impressive as they are all Earthgrazers, skimming the atmosphere almost horizontally overhead,” notes Brown. “Earthgrazers tend to be slow and very bright.”

It turns out that June is the best month of the year for daytime meteor showers. When the Arietids subside, another daytime shower will take over: The zeta Perseids peak on June 13th. And then another: The beta Taurids on June 29th.

The beta Taurids are particularly interesting because researchers suspect it may be responsible for the Tunguska explosion of 1908. This June the Taurid debris swarm will make its closest approach to Earth since 1975. Many astronomers, including Brown, will use large telescopes to search for signs of hazardous objects as the swarm passes by.

Stay tuned for updates.

End note: (1) Tunguska was a dramatic example of a daytime meteor. It took 30+ years after the explosion, however, for the field of daytime meteor studies to gain its footing. Brown explains: “The first daytime showers were observed and recognized by astronomers at Jodrell Bank shortly after World War II, really kickstarting the field. As early as 1940, studies of the orbit of the nighttime Taurids suggested the stream should intersect the Earth during the day in June. At that time, predictions were made by Fred Whipple of a daytime component to the Taurid stream in June (the Beta Taurids/Zeta Perseids). In the 1970s, the peak date for the Beta Taurids (about June 30) and the radiant location were matched by Lubor Kresak to the Tunguska fireball–at which time he posited a link between the Beta Taurids and Tunguska.”