Oct. 31, 2023: (Spaceweather.com) Imagine waking up to this headline: “Half of Earth’s Satellites Lost!” Impossible? It actually happened during the Great Halloween Storms of 2003.

Turn back the clock 20 years. Solar Cycle 23 was winding down, and space weather forecasters were talking about how quiet things would soon become. Suddenly, the sun unleashed two of the strongest solar flares of the Space Age–an X17 flare on Oct. 28 followed by an X10 on Oct 29, 2003. Both hurled fast CMEs directly toward Earth.

A CME heading straight for Earth on Oct. 28, 2003. The source was an X17-flare in the magnetic canopy of giant sunspot 486. Image credit: SOHO. Movie

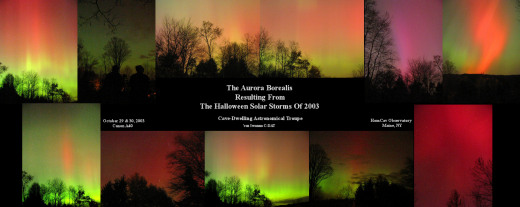

Traveling 2125 km/s and 1948 km/s, respectively, each CME reached Earth in less than a day, sparking extreme (G5) geomagnetic storms on Oct. 29, 30, and 31, 2003. Auroras descended as far south as Georgia, California, New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and Oklahoma: photo gallery.

Onboard the International Space Station, astronauts took shelter in the hardened Zvezda service module to protect themselves from high energy particles. Meanwhile, airline pilots were frantically changing course. Almost every flight over Earth’s poles detoured to lower latitudes to avoid radiation, costing as much as $100,000 per flight. Many Earth-orbiting satellites experienced data outages, reboots and even unwanted thruster firings. Some operators simply gave up and turned their instruments off.

There’s a dawning awareness that something else important happened, too. Many of Earth’s satellites were “lost”–not destroyed, just misplaced. In a 2020 paper entitled “Flying Through Uncertainty,” USAF satellite operators recalled how “the majority of satellites (in low Earth orbit) were temporarily lost, requiring several days of around-the-clock work to reestablish their positions.”

Active sunspot 486 was the source of the 2003 Halloween storms

How did this happen? The Halloween storms pumped an extra 3 Terrawatts of power into Earth’s upper atmosphere. Geomagnetic heating puffed up the atmosphere, sharply increasing aerodynamic drag on satellites. Some satellites in low-Earth orbit found themselves off course by one to tens of kilometers.

Most satellite operators today have never experienced anything like the Halloween storms. That’s a problem because the number of objects they need to track has sharply increased. Since 2003, the population of active satellites has ballooned to more than 7,000, with an additional 20,000+ pieces of debris larger than 10 cm. Losing track of so many objects in such a congested environment could theoretically trigger a cascade of collisions, rendering low Earth orbit unusable for years following an extreme geomagnetic storm.

Now that’s scary.

more images: from Andreas Walker of Rossbüchel, Switzerland, Europe